Why brands are launching their own resale platforms

Are brands with owned resale platforms driven by sustainability, or do they just want to sell us more stuff?

Last year, M.M.LaFleur launched Second Act, its resale platform. (Photo: M.M.LaFleur)

CIRCULAR SHOPPING

Allbirds doesn’t really do sales — but it is possible to nab a bargain on the sneaker brand’s website.

In February, it launched a platform called ReRun, stocked with “gently used” footwear that has been returned to its stores. Right now, a pair of red women’s trail runners that would normally cost $138 are listed for $99, while there are plenty of men's wool loungers going for about $60.

In exchange for handing over their old shoes, Allbird's customers receive a $20 discount on purchases of new items.

Sales of secondhand clothing have been rising thanks to platforms like Depop and The RealReal, which have made the experience of browsing for new-to-you wares much nicer than having to trawl through eBay. Now, brands are working with tech firms to incorporate resale directly into their own websites.

Ganni has just launched its own resale marketplace with Reflaunt, a tech firm that connects brands with secondhand marketplaces around the world. Another Tomorrow launched its resale program last year; its clothes feature scannable QR codes so customers can make sure their secondhand items are really from the brand. Also last year, bag brand Dagne Dover and women’s clothes brand M.M.LaFleur both launched peer-to-peer resale platforms using tech from Archive, which describes itself as “building an operating system for resale.” Even furniture brands, like Floyd and Sabai, are getting in on the resale action.

According to ThredUp, the clothing resale market (which doesn’t include sales of secondhand clothing from thrift and charity stores) was valued at $15 billion in 2021, while 33 million shoppers bought secondhand clothing for the first time in 2020.

Over the next three years, the company expects the market to grow 11 times faster than the broader retail sector as customers become more aware of the impact of their consumption.

Why are brands setting up resale platforms?

The fashion industry has an enormous environmental impact. In 2018, it’s estimated that it emitted a whopping 2.1 billion tons of CO2 — 4% of the world’s total carbon emissions. An enormous amount of water is also consumed in the process of growing cotton, while toxic chemicals used to dye fabrics can end up in local water systems. After all that damage is done, many of the clothes we buy don’t even get worn.

McKinsey says the fashion industry will need to cut annual carbon emissions to do its bit in limiting global warming. Reducing production is an obvious solution and resale — in theory — could make that happen while still allowing businesses to generate profits.

Legislation taking aim at overproduction in the fashion industry is also being introduced. In France, it has been illegal to destroy unsold products since January 1st of this year, while in Sweden manufacturers will soon have to pay to collect textiles at the end of their life.

Brands that introduce resale are not only getting ahead of such changes and sending a message about their stance on sustainability, they are also taking ownership of a process that would normally happen outside of their control.

Adele Tetangco, the cofounder of ethical fashion brand et Tigre, says that people were already reselling her brand's items on Instagram before she introduced resale to its website in 2020.

“I thought this was a great way to take ownership of that. That was the motive,” she says. Shoppers can log in to their account to see the items they’ve previously purchased, and set up listings that pull in et Tigre’s photos and item information. Once a product sells, which Tetangco says is typically within four days, customers receive the money as store credit. “Not only is it bringing circularity back to your business, but it’s also increasing conversion with customers you already have, because they’re coming back to shop for something else,” Tetangco says.

M.M.LaFleur lets customers choose between receiving 70% of the resale price as cash, or getting 100% as store credit. Founder Sarah Miyazawa LaFleur says that 72% of sellers choose store credit, and normally end up spending about three times the value of that credit the next time they shop with the brand. “I feel like one of the reasons I sometimes end up not buying clothes is [because] I look at my closet and say, 'Oh my god, I have so many clothes I don’t need to buy new,'” she says. Resale provides customers with a solution for that problem.

Dagne Dover says that so far 1,100 bags have been sold on its resale platform, and that 54% of sellers opt for store credit instead of cash. Following the platform's launch in September 2021, cofounder Melissa Mash says about half of those earliest sellers then spent their store credit on “new product from us in the holiday season.” “It really does seem like they’re clearing out their closet in order to make space for more,” she adds.

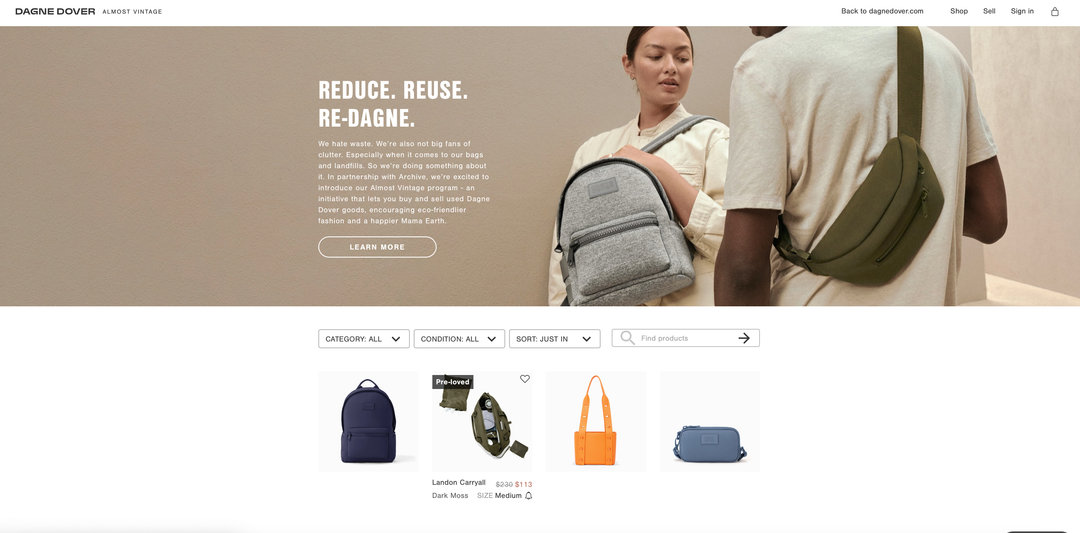

Dagne Dover's resale platform, Almost Vintage. (Screenshot: Dagne Dover)

Conscious consumption, or just consumption?

So if brands are using resale as a way to lock customers in to future purchases of new clothes — can it really be considered a sustainability effort?

Stephanie Crespin, the founder of Reflaunt, agrees that sustainability is unlikely to be the main driver behind an individual brand’s decision to start offering customers secondhand products. In fact, the business case is much more around “increasing the lifetime value of these customers and upsell them to higher value products”, she says.

“There is a crisis among brands around loyalty,” she adds. “They’re spending tons of money on Facebook ads, whereas with a secondhand service they’re able to re-target and re-convert customers when [they] have disposable cash and space in their wardrobe.”

Critics of resale platforms argue that they do nothing to shift consumer mindsets away from the pursuit of new products — in fact, they say it makes it easier for people to continue binge shopping by reducing prices.

Crespin, however, believes the growth of resale could inspire a mindset shift among consumers, where they will shop with the resale value in mind. Fast fashion brands, considered the worst offenders when it comes to environmental impact, would therefore struggle to sell their low-cost items in this environment. “Secondhand is building visibility on the value of a product,” she says. “Consumers understand that if they buy a product that doesn’t hold its value, it can’t be resold.”

“If we can get these pieces that are truly meant to last for a long time into the hands of new women who might not consider us at full price, that’s a win-win,” says LaFleur, who says that resale has essentially broadened the audience for her brand. “Maybe one day they will also become full-price customers.”

This theory relies on fast fashion shoppers starting to purchasing with these more expensive brands.

The true test will come when brands across the board — not just those who market themselves as sustainably and ethically minded — begin to adopt resale. In February, U.K. fast fashion brand PrettyLittleThing announced that it will be launching a Depop-style marketplace where customers can sell their old items in exchange for shopping credits. Its popularity should be closely monitored.